Of shells, dells and wells

Of family and other animals…

After an April that impersonated June, May, it seems, has decided to swap with March this year. Pardon me, please then, for grabbing your hand and pulling you away from the fireside, but I need to show you the windowsill.

There… Do you like it?

Its sixteen inch depth hinting at the solidity of the walls, in my childhood it was home to the budgie – an at best apathetic and at worst quite cantankerous creature, dedicating his existence to taking the ‘joy’ out of Joey – with little resultant ecstasy.

Not that I blame him, retrospectively – I’d sooner chew grit than keep a bird in a cage now – but at the time I was oblivious to such welfare considerations and simply longed for interaction. Any attempt at interface though – be it verbal or physical – was rejected with either indifference or outright assault.

Actually, it’s remarkable that I grew up an animal lover at all, what with a budgerigar that bit, a rabbit that scratched (people) and a semi feral cat that did both. Tim completed the brood: a belligerent Jack Russell who lived to fight, growl and roll in manure. He was, I suspect, desperate to shed the delicate l’air de Fairly Liquid, with which he was bathed every time he found a new source of dung – either that or he accidentally overheard someone – pointlessly – ask Joey ‘who’s a pretty boy? and took it to his macho little heart…

He scratched too, but not in an aggressive way, favouring his jaws as a far more direct means of communicating displeasure. This was, incidentally, back in the days when growling and biting were considered quite normal thing for country dogs to do, and reporting being bitten was more likely to lead to enquiries as to what you’d done to provoke it than demands for the poor beast to be destroyed.

Anyway my mother, blaming fleas, upped the dog-scrubbing stakes – and yet he continued to scratch – indeed scratched all the harder it seemed, till patches of skin began to show strawberry through his vanilla-with-a-hint-of-guano coat. It took a visit to the vet to convince her that the cause of Tim’s irritation was in fact her over-washing – proof that hands that do dishes can feel red as your face… and consequently, Tim lived out his days happy as a terrier in shite.

Back at the windowsill, once the budgie had shuffled off his mortal coil, kicked the bucket, run down the curtain and joined the choir invisible – any one of them in itself an act more diverting than he’d ever managed in life – the space he left became a memorial garden of houseplants. In my opinion almost as unnatural as caged birds, I remember carrying them all outside one mild but rainy day soon after mum died, knowing that this was theoretically good for them. Forgetting to bring them back in again, ultimately, wasn’t.

Of places and spaces…

It was also soon after her death – the first Christmas in fact – that we decided to move the table from where it had always dominated the centre of the room over to abut the windowsill. My father had pre-deceased my mother by less than two years and the growing number of gaps around it yelled loss at every mealtime. With one of the table’s long empty ends pushed against the wall though, my father’s space disappeared completely, whilst my mother’s was replaced by the TV corner. And rather than stare at a plain, bare sill – now the obvious viewpoint – a small, metal Christmas tree was found which fitted rather beautifully… something new and bright in a dark old year.

But with Christmas’ passing, the sill wailed emptiness again – and so began a new tradition of its contents changing through the seasons – an indoor reminder of the precious turning of the year.

Quite why the cycle of the year feels so important to me I honestly don’t know; links between light-induced serotonin and mood, highs associated with increased levels of activity and the recent discovery of seasonal change in dopamine levels may explain why we experience SAD, or feel ‘full of the joys of spring’ (tra-la) – but describe only the mechanisms – it’s a how, not a why answer. And if it’s the only answer it should cause me to cling to spring and summer, eschewing autumn and winter – which I don’t.

Besides, I have two natural low points in my disposition’s cycle, one of which seems quite unrelated to endocrine activity. The first, predictably enough, is January, so aptly dubbed ‘the Monday of the year’. Let us banish it forever, or spend it in sleep.

My double dip’s second trough, however, arrives inexplicably in early July and will stay with me throughout August – as if something within me registers the shortening of days and mourns the dying of the light. Come September, I rally again, hugging autumn with open arms, but seem doomed to spend each ‘high’ summer on a low of both energy and emotion. Explanations – or just empathy – on a postcard from your favourite holiday destination please; I will be staying at home…

Of turning and re-turning…

Returning to the turn of the year, perhaps it’s simply a case of needing contrast and change to hone appreciation; ‘no pleasure endures unseasoned by variety’ wrote Syrus, long before it became the overused spice of life. And yet I suspect that much of what I cherish is actually the familiarity of the season’s markers – the known in the unknown, the affirmation that although time passes, the song of its cosmic ticking remains a familiar lullaby.

Out seeking May blossom last week, I was suddenly surrounded by swallows tumbling crazily through evening sunlight and felt my own gladness soar with their aerobatics. The first snowdrops, the midsummer opening of the Slade rose, grown from a cutting from my great-grandmother’s garden, the reappearance of starlings in the back yard, filthy though I know they will leave it – all engender a wish to smile ‘hello again’- and indeed I often do.

The new is greeted too of course – this year a blackcap has decided to nest in the quarry garden and repays me for the hospitality with fluting song at frequent intervals. I’m trying to feel as welcoming towards the woodpigeons camping out in the huge old spruce too, but their co-cooo-coook, co-cooo-coook can get a bit too-tooo- too much. I wonder what variety the spice of pigeon pie is?

But though new for my garden, their presence and behaviour is still part of the larger, seasonal theme – they are still birds nesting in spring, and if I knew only that birds do that, I would find them unremarkable. It’s having an appreciation of what is everyday and commonplace for this corner of the world then – knowing what usually nests here – or when I’d expect a particular plant to bloom – that enables me to identify the unexpected, the early or the late. And with that intimacy of knowing come both a deep sense of connection and the ability to wonder at the truly unusual when it does happen.

Imagine my delight that the first living thing I saw this Beltane morning was a young rabbit, lolloping down our road before turning into the neighbour’s driveway opposite and stopping for breakfast on their lawn. Only forty-plus years of staring through the same window enabled me to know that this was a first – that baby rabbits just don’t do that in this street. Or at least they haven’t until now.

It also made me smile that a week precisely had passed since I was texting the very same household to warn them that I’d just seen a suspicious looking rabbit hanging something from their rhododendron, and that the girls had better investigate before whatever it was melted… ‘Did you really see the Easter Bunny?’ asked the youngest. ‘Ach I only caught a glimpse of its ears,’ I replied; who am I to split on hares?

So ok, that’s what I get from the cycle of nature in itself… a sense of connection and wonder in bunnies… but why do I also want to impose artificial markers on the year – to celebrate the solstices and the days known as Imbolc, Beltane, Lammas and Samhain as well as joining in with Christmas and Easter traditions? I am neither pagan nor wiccan and have no more belief in a mother goddess than I do in the father, son or the wholly ghostly, although I worry more that I might be offending a Her than a Him by saying so…

Perhaps part of it is ancestral memory: a sense of how important these days – as opportunities for both exerting influence and seeking prognostication – must have been for those who really relied on the land – not only for their livelihoods but also sometimes for their lives.

Growing our own foodstuff – in this country at least – is largely a hobby these days. But anyone who gardens – whether for leisure or through necessity – knows that although we do sometimes end up reaping what we sow, we are, too, subject to the slings and arrows of air and soil-borne pestilence not to mention the mercy of the weather. We play dice with our gods and our gourds.

My own stakes are low – if my potatoes are blighted or slugs devour my lettuce-lings, I pop into the supermarket or the garden centre without a second thought. But it was not always so. Growing up, the success or failure of the household’s vegetable crops, the level of egg production, good honey and fruit harvests and the safe storage of both produce and seed over the winter months were all vital to the family budget. And for others, even today, the stakes are higher still; people absolutely dependant on soils and pastures which can, overnight, become desert or flood.

Offered the chance, then, that performing certain ritual acts may influence the future – that driving the cattle through the embers of the Beltane bonfire will keep them free of sickness, that honouring the dead at Samhain will dissuade them from mischief in the coming year, or that spreading Imbolc ashes on the land will help ensure a good harvest, you do it.

And although I share none of these beliefs, I have of course my own human faiths, fears and frailties – along with a quite profound sense of being glad for what I have, have had – and hope to have, still. Personally then, the odd ‘special’ day is a chance to pause, reflect, appreciate and anticipate – albeit through hope rather than prayer or incantation.

Of yolks, restraint and pillories…

There is also, of course, the opportunity for a bit of feasting and decoration – welcome chances for creativity – to make things that taste or look nice and to share and enjoy them with people I love. Eggs, unsurprisingly, have been central to both just recently.

Googling around Easter, I’m constantly bemused by the number of sites asking ‘why do we have eggs at Easter?’ Am I alone in thinking it would be quite remarkable if we didn’t? As universal symbols of new life, creation and procreation, their decoration and giving has certainly been part of spring festivities since Zoroastrian times and, I’d hazard a very large bet, for much longer besides.

I was equally bemused then to find a site – from the Meaningful Chocolate Company offering people the chance to buy ‘The Real Easter Egg’, a Fairtrade chocolate experience featuring the story of the crucifixion on the box. Two years in development, the egg’s packaging portrays pink people strolling through a sunlit park surrounded by rabbits, chickens, butterflies and ducks, overlooked by a green hill (far away).

I’m not going to knock it – they do give a proportion of what they make to charity. I’m just a little bewildered by what young recipients might think – and what the company’s next venture might be, given their promise that ‘The Real Easter Egg is the first in a range of meaningful chocolate products…’ Valentine hearts bearing tales of bloody martyrdom, perhaps, or a chocolate nativity set?

I, for one, can’t eat anything chocolate with eyes, leaving me sighing when I’m given yet another one of those cute little Lindt golden bunnies. I have years’ worth of them now, vying for dustiness and threatening to breed. Nor will I eat spring lamb at Easter; having cooed at them over farm gates for weeks, I just can’t stomach the thought. Nothing should die before it’s felt the true warmth of the sun.

‘But eggs are chickens that have never felt the sun’ points out Tom as I hard boil my second dozen, ready for decoration. I could, of course, have blown them, but the lividity of my face after attempt number one made the saucepan option seem so, so much more attractive. And at least they’d feel warm as they dyed…

It also set me thinking about teaching your grandmother to suck eggs, and what a cruel and unusual thing to do that would be… ‘And then you inhale deeply, nan… and try to spit before you vomit, choke or contract salmonella…’

My original plan for embellishment (who, me?) was a wax-resist method capable of producing minutely detailed decoration particularly popular in Slavic and eastern European nations. Then I realised quite how long applying said wax with the head of a pin was going to take – with or without assistance from however many associated angels – and bowed out in reverence to those with more patience. I wonder if there’s a Russian saying which translates as ‘go teach your babushka to paint eggs’?

A pack of OHP markers – sadly redundant since Powerpoint faded the creativity out of presentations – along with some old metallic lacquer pens were, then, pressed into service once more. Oh how I adore stationery – especially when it still works after years in a drawer. In fact if Jude heaven had only four shops, then one of them would have to sell paper, pens, pencils and art materials. What would be in yours?

My other three would be a nursery-cum-garden centre-cum-florist, a bookshop with both new and second hand volumes (in fact every book you ever wanted to find would be in it – it’s just you wouldn’t actually know that… so that you could continue to enjoy the thrill of the search) and an outlet offering both pre-made music and the means of making it. The fifth of the six – this being heaven after all – would be a small foodstore which knew exactly what you wanted to eat even before you did and would have it ready for collection, obviating the need for all that traipsing up and down with a trolley. In fact the only choice you would have to make would be which of their coffees you’d like freshly ground.

The last shop would sell things in boxes and cupboards – and boxes and cupboards for their own sake. Some of them would be too small to hold anything much, and some of them would be large enough to hide in – with our without company – but each would contain something of necessity, beauty or just sheer fascination.

An ante-room, meanwhile, would be devoted to sets of drawers and desks, none of which would contain a beetle attached to a nail by a piece of cotton… I’ll just whisper ‘The Wicker Man’ in case you were trying to remember, dancing round its own maypole…

And then of course I’ll get distracted and Google that particular scene… and discover in so doing that most internet entries describe it as a beetle tied to a nail by string. I mean I ask you – have you ever tried tying a piece of string ’round a beetle? Nor, I hasten to add, have I: life is too short. Unless, of course, the beetle in question were of a particularly large variety, when a lasso of stout rope might be the preferred securing medium.

‘The little old beetle goes round and round, always the same way, you see, till he ends up right up tight to the nail, poor old thing…’ sighs young Holly – in parallel of course with Sergeant Howie being lead round and round in circles by the weird islanders, whilst all the time getting drawn closer and closer to the totem of the wicker man…

Meanwhile, back at my shopping mall at the end of the universe, it drew an ‘oh! gosh!’ from me to discover that the word ‘stationer’ came from the Mediaeval Latin stationarius – i.e. someone with a permanent, fixed bookshop as opposed to an itinerant trader or peddler who travelled about selling their wares. The stationers were, then, stationary… indeed permanent markers, you might say…

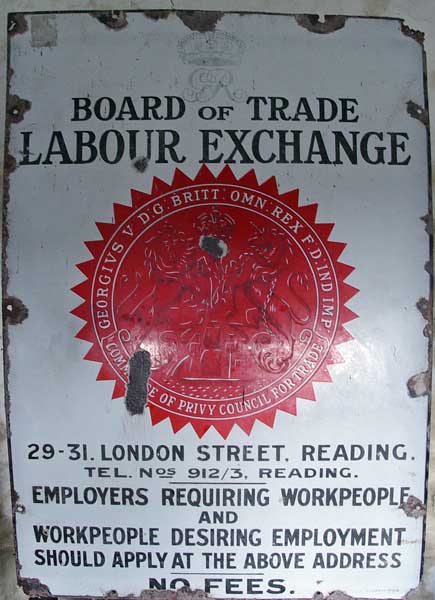

Peddlers, incidentally, didn’t necessarily peddle any more than hawkers spat, but I have heard it rumoured that both professions are to be revived and added to the list of job options offered by the coalition government under its new Work Programme, along with those of vagrant and vagabond. Let us hope the DWP never encounter the ‘Caveat or Warning for Common Cursitors, vulgarly called vagabonds’ by Thomas Harman – a 1566 catalogue of beggars along with their means of raising funds.

Amongst them they would find the ‘Demaunder for Glymmar’ – a woman who pretends to have been injured or to have lost her possessions through fire, the ‘Counterfet Cranke’ who feigns the falling sickness and the ‘Abraham Man’ – named after the ward at Bethlehem Hospital – someone who claims to be an ex-inmate of a lunatic asylum and relies on others’ fear to make them respond to his pleas.

‘A Dell’ meanwhile was a wench ‘not yet known or broken’ – i.e. still a virgin. Harman holds out some sympathy for those who have fallen into Dell-dom e.g. ‘by the death of their parents’ but little hope for ‘wyld’ Dells – i.e. those born into begging who ‘muste of necessitie be as evil or worse than their parentes, for neyther we gather grapes from greene bryars, neyther fygges from thistles.’ Ah well, it could be worse – a dell could be a singer who names her albums for her age… and I bet she finds new inspiration once we’ve been treated to ‘35’…

‘Hokers’ were not what you might expect. For a start they were male – indeed not just male but also possessed of a pole of great length, with a hook at one end, for… um… hooking. By day they would travel door to door, ‘well noting what they see there’ and by night they would return for their through-the-window fishing expeditions – hence their alternative name of the ‘anglear’.

Another specialist was the ‘Dommerar’ – someone who posed as a mute, folding their tongue within their mouth to make it look as if it had been cut. Dommerars were, he warned, mostly Welsh; a difference then between their being able to speak and being understood.

‘These Dommerars… will gape, and with a marvelous force will hold down their toungs doubled, groninge for your charitie, and holding up their hands full piteously, so that with their deepe dissimulation they get very much’ explains Harman. He goes on to describe an encounter with one Dommerar when he suggests to a local surgeon that they should ‘knit two of his fingers together and thrust a stycke between them, and rubbe the same up and downe a little whyle’. They decide instead though to hang him by his wrists ‘and hoysted him up over a beam. And there did let him hang a good while (til) at length for very paine he required for Gods sake to let him downe’.

Our brave defender of the rich then ‘tooke the money I could find in his purse … which was xv. pence halfpenny, being all that wee could finde’ and delivered him and a companion to the ‘justicer’ to be pilloried and ‘well whipped, and none did bewayle them’.

One of the Kentish landed gentry and also a tax inspector, Harman implies in the Caveat that he is a JP although no evidence exists to support this. Surely not a ‘Blagger Bogusta’?

I have also noted, in passing this way, that the word vagabond comes from the Latin adjective ‘vagabundus’ – ‘inclined to wander’, just in case I ever need an alternative title for my blog…

Of going a little wild…

Anyway, back at the windowsill, the seasonal display started the week innocently enough – some eggs, my hare… a fine bunch of spring daffodils… quite lovely. As Easter came and went though and Beltane approached – dear Beltane, fecund and wild – the daffodils wilted and the hare looked a tad plain…

‘I need a maypole’, I decided, glad I’d thought to keep the ash wand snipped from its roots in the talcen (welsh for forehead, the gable-end of a house and its environs, the latter being, thankfully, the spot where I’d found this particular specimen growing). Wedged into a stack of earthenware pots and bedecked with ribbons and peacock feathers, it did very nicely. A garland for the hare and the replacement of the daffodils with an exuberant bunch of lilac, apple blossom, masterwort and pittosporum completed the transformation… the windowsill had been resurrected… ‘Will people think I’m a bit mad?’ I asked Tom. ‘A bit?’ he replied.

Pittosporum, in case you’ve never encountered it, is about as Beltane as it gets. Content to be just a small, evergreen tree eleven-out-of-twelve, in late April it bedecks itself with dark, chocolate-button flowers which smell (oh so sweetly) only at night. Around her base I grow a pale, early-flowering honeysuckle, the perfect torc for her strangeness and charm…

To appreciate her properly you need stillness, allowing her perfume to hang heavy on the night and intoxicate – or to bring a few sprigs indoors, apologising profusely as you cut them, of course. You must never ever be tempted to do the same with Hawthorn, though, May blossom being considered extremely unlucky if it is allowed to cross your threshold.

Nor must you bring eggs into your home after dark – a bit tough on those used to doing their winter shopping after work. The first mention of this superstition appears in 1853 in ‘Notes and Queries’, where it is recorded that ‘a person in want of some eggs called at a farm-house in East Markham, and enquired of the good woman of the house whether she had any eggs to sell, to which she replied that she had a few scores to dispose of. ‘Then I’ll take them home with me in the cart’ was his answer; to which she somewhat indignantly replied, ‘That you’ll not; don’t you know the sun has gone down? You’re welcome to the eggs at the proper time of day; but I would not let them go out of the house after the sun has set on any consideration whatsoever!’’

The People’s Friend, in 1882, states that ‘Nothing is more unlucky than to meddle with eggs after dark’, whilst P.S. Jeffrey writing his ‘Whitby Lore’ in 1923 relates how ‘In some remote villages it is still considered unlucky to buy eggs after sunset, and any enquiry for eggs at this advanced hour is resented as bringing ill-fortune to the house’… a promise that almost makes me want to stop off at Tesco’s in after dark each night and demand a dozen of their finest.

The belief that when eating them properly – boiled for breakfast, that is – you must not break them at the pointed end is recorded as far back as 1650 and as recently as 1923 when in Taunton, the belief was recorded that cracking an egg at the ‘small end… will cause you keen disappointment’.

To consume the first egg ever laid by a hen was to attract good fortune whilst to eat the last was predictably unlucky… especially if it were to contain a Cockatrice…

‘He will often be in fear, too, lest a Cockatrice should happen to be hatched from his Cock’s Egg, and kill him with its baneful aspect,’ warns Swiss theologian Werenfels in his ‘Dissertation upon Superstition’ in 1748.

The said Cockatrice evolved as times turned; in the Roman era it was considered to be a small serpent – albeit one capable of killing with just a breath or a glance. By the twelfth century it was variously interchangeable with crocodile or Basilisk, thanks to a mistranslation – only later settling for the shifted shape of the body of a dragon and the head of a cock.

Its power to petrify extended to all but the weasel, and it could be slain by glancing itself in a mirror, or by the cry of a cockerel (‘unhand my head at once, you cad…’). More recently it is a ‘Slayer monster that require level 25 Slayer to kill. They frequently drop limpwurt roots, which is their main food source… cockatrice skin must be collected and cleaned for the Odd Old Man.’ Now there’s a vagabond Harman missed…

It’s also made appearances in the BBC’s ‘Merlin’, in ‘Harry Potter and and the Chamber of Secrets’ and… wait for it… in ‘My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic’. Go tell that to the horse Daniel Radcliffe befriended in Equus…

I hope before riding, that he made a point of eating an even number of eggs, for to do otherwise would ‘indanger the horses’, according to Camden’s Britannia in 1586. It goes on to record that any horseman eating eggs should wash his hands immediately, and that jockeys are not allowed to eat eggs, however fastidious their personal hygiene.

They could of course use them for predicting the outcome of a race however, employing oomancy…

The use of the liminal, living-yet-not contents of an egg to look into the future is first documented in 1684, but in terms of being ‘the foolish sorcery of women’, which makes me suspect that its practice long pre-dates the account in Mather’s Illustrious Providences. ‘It were much better to remain ignorant than thus to consult with the devil,’ he concludes.

Frequent and similar accounts continue to pepper the literature of folklore for the next three centuries, all describing the interpretation of the shapes formed by egg white when dropped into water, although any egg suckers or blowers will, I suspect, raise an eyebrow at Henderson’s 1866 instructions to ‘perforate with a pin the small end of the egg, and let three drops of the white fall into a basin of water’ – as if gravity were likely to suffice. ‘They will diffuse,’ he explains with confidence in his Notes on the folk-lore of the northern counties of England and the borders ‘into fantastic shapes’ from which ‘the initiated will auger the fortunes of the egg dropper’.

Someone dropping an egg accidentally, meanwhile, had better break another – but not another, for

‘Break an egg, break your leg,

Break three, woe to thee,

Break two, your love is true’

Break four, omelette galore, perhaps?

Or break four, eggs benedict for two, an apt Beltane brunch, particularly if the weather allows it to be eaten in the garden, in the shade of the pittosporum, as it did this year. Prognostication wise however, the experience would suggest that ‘if on Beltane morn you can break your fast outdoors, then for thirty days it will remain too cold to even think of doing so again.’

Eggs benedict, for the uninitiated, is a pyramid of crumpet (halved, toasted and copiously buttered) ham, quiveringly soft poached egg and hollandaise sauce – in that order. In totality, it probably amounts to the most sensuous dish I have ever had the utter pleasure of swallowing. But how to crown it? How to make it perfect for Beltane? Inspiration suddenly struck, courtesy of a punnet of strawberries …

Almost perfect at least, for the old hawthorn at the top of the steps remained stubbornly shut, refusing to greet the new month. In fact I had to travel a mile inland to beg a small sprig of blossom for the table. Intuitively wrong, I know, as most things seem to open earlier slap bang on the coast, but then the opening of the May has always puzzled me.

I suspected for a while that it might break in an east-west wave across the country, for that’s certainly what it seems to do locally. Maps of hawthorn bud-break at the Woodland Trust’s site however (link below) suggest a far more random pattern, kicking off around Wiltshire, spreading first east-ish and then west-ish as well as slowly north, with plenty of exceptions.

Traversing the breadth of the land on the 12th – old May Eve – from west to east and, happily, back again, allowed me to observe for myself the quality of blossom stain from beauty to blemished to bruised to brown. And what became obvious, very quickly, was the very local variation, seemingly independent of aspect, shade or shelter. Whilst one tree in a hedgerow would be only just bubbling into blossom, another would already have the air of deflated champagne to it, blending perfectly with the sallow sheep.

The sallowness of sheep is, of course, no reason to shun them. Their hue, given their lack of access to plumbing or peroxide, is understandable. Shallow sheep on the other hand are best avoided: you trust them, you share your heart with them, you pour your hopes and dreams out to them and they walk away with just a ‘bah’…

Forgive me… but I was so restrained with the eggs… ‘nest’-ce pâques?

Some of the hawthorn’s variation in blooming is doubtlessly due to there actually being three fairly common varieties in the UK – the native hedgerow variety, Crataegus monogyna, an earlier flowering cultivar introduced from the Netherlands purely for hedging and finally the woodland hawthorn, Crataegus laevigata. Now only found in ancient woodland and in very old clay-footed hedges, C. laevigata would have been the more common in the early Middle Ages – the era from whence most plant-lore springs – for it wasn’t until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that extensive Enclosure Acts saw almost a quarter of a million miles of hawthorn hedges being planted in ribbons around once common land.

The woodland hawthorn also blooms earlier – so, depending on where you live, might more reliably have been gathered on May Day old before the Gregorian calendar was introduced in 1752.

It is also smellier. All hawthorn gives off the gas trimethylamine – the compound which puts the fishiness into fish and one of the first chemicals formed in decaying tissue after death. It is reported of the woodland variety however that ‘although in smell quite like the other form when gathered, it….stink(s) of putrid flesh soon after: – sometimes within about half an hour.’ The taboo concerning bringing Hawthorn across the threshold starts to sound quite sensible…

But trimethylamine is also, writes Richard Mabey in his Flora Britannica ‘the smell of sex – something rarely acknowledged in folklore archives, but implicit in much of the popular culture of the hawthorn…. The hawthorn or may was the special object of attention at May Day ceremonies that centred on the woods, the maypole and the May queen… In contrast to Christmastide greenery and Easter willow, it is a plant kept outdoors, associated with unregulated love in the fields rather than conjugal love in the bed.’

I’ve also noticed amongst the folklore a recurrent, quite specific belief that bringing may blossom into the house will cause your mother to die, one of its welsh folk names being ‘blodau marw mam’ (literally ‘flowers die mother’) and similarly ‘mother die’ in England. Echoes here perhaps of Beltane being the time of the new maiden or white goddess, resplendent in her creamy garlands?

On a more cheerful note, some say the nursery rhyme ‘here we come gathering nuts in May’ actually refers to the gathering of ‘knots of may’ whether for decoration or matricide, whilst others again think it relates to pignuts: Conopodium majus. Also called the ground nut, cat nut or earth nut, pignuts were traditionally grubbed up from amongst the bluebells around this time of year, a good source of carbohydrates, particularly welcome in the weeks before the first new potatoes are ready. (don’t try it though, for bluebell bulbs are quite poisonous as well as quite precious…)

Mabey writes that ‘digging for the dark-brown tubers of the pignut used to be a common habit amongst country children. The nuts are usually between six and eight inches under the earth, and eaten raw, their white flesh has something of the crisp taste of young hazelnuts… They would be cooked in a Dutch oven with rabbit joints.’

Noooo! Do not eat bunnies in springtime! They have baby bunnies in them – some wrapped in gold foil… Cook them instead with red wine and blackberries in autumn… after they’ve felt the warmth of the sun…

Meanwhile, I’m going to make a suggestion… perhaps I’ll even send it to Nick Clegg for goodness knows, he needs a popularist cause at the moment… I’d like to propose that Easter is fixed as being the penultimate weekend in April, so that it will always be followed by Mayday a week later.

It will be decreed that the royal family – in return for their board and lodging – will now regularly perform some sort of diversionary antic on the Friday between, so continuing to provide three quarters of the British workforce with the chance of ten days off in return for three days’ leave. We need, I think, the opportunity to celebrate spring properly: I am not alone, I know, in noticing the general uplift in community mood during that period of late April.

Parliament could do it – in fact have already done something very similar – with Easter’s date actually having been fixed in statute as the Sunday following the second Saturday in April for almost ninety years now. The Easter Act of 1928 was, however, never implemented. Repeal it then, legislate anew, and give us back Beltane to boot…

I, whilst waiting, will continue to chase the May…

There’s a charming little valley not too far from here which has something of the feel of the otherworld to it. Protected by a ‘private road – keep out or you may be banjoed’ sign (well ok, not quite, but there’s something of that air to its hand-painted legend) only locals ever venture there, and most of them simply don’t bother. It’s consequently home to vast lollops of over-trusting rabbits, myriad birds of prey feasting on the aforementioned, some wild, wild sheep and a confetti of old hawthorn trees, punctuating the poor pasture with their bright exclamations this time of year.

I say ‘time’ but what I mean is actually time-ish, for I first found it in its most magical of states some five or more Mays ago – and keep trying to capture it in the same mood since. I say ‘keep trying’, by which I mean almost obsessive re-visiting from late April onward, ‘there may be may’ being the motto by which my early summer has become governed. Never since though have I witnessed the arc of the sun and the mysterious blossoming so perfectly entwine – all the more reason to anticipate the day when they do again with particularly keen hunger. May I keep you posted?

My other predictable Beltane pilgrimage is to the old well at Llanllawer. Not quite a ‘clootie well’ just yet, it’s showing signs of getting there, recent visits revealing many small strips of cloth having been attached to the wooden gate at its entrance. A stone, too, simply inscribed with a hare had been offered there this year.

I simply left flowers of the spring, and in closing will do the same for you…

The only down side to your delightful posts is All the comments that sputter thru my head as I read, are completely lost to me by the end!

~laughing~

such as” I wish I could be a hermit in july, but I would be out of dosh by october”

and ” not all vagabonds who wander are lost”

oh and I do adore your puns!

Thanks for the treat and the view inside and outside your window…

I’m smiling at your comments yet again; thank you; you have immense generosity and patience.

I completely agree re. vagabonds – if I didn’t feel so deeply rooted I too might well wander – and am sad that society often judges those who do.

I don’t disappear completely during July and August -in fact might even set myself the challenge of finding blogging inspiration within them this year. And am so glad to find that you are writing…